ABCs of Psychiatry: Schizophrenia

An intro post to schizophrenia from a pharmacy point of view. Pharmacy treatment options, side effects, and drug interactions are discussed.

Wherever you learn about medications (pharmacy program, a pharmacology course in nursing school, throughout medical school, etc.) everyone has subjects that do not seem to “stick” in their brain. For me, psychiatry was one of those subjects (ironically); therefore, the first clinical topic I want to cover with you is schizophrenia!

Disclaimer: This post is meant to provide an overview of a clinical topic that may include (but is not limited to) information on pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, clinical pharmacology, medication management, adverse effects, and clinical pearls. References are included at the bottom of each post. This post is not to be used as medical advice for direct patient care, but as a guide for learning and discussion.

If you would like to listen to the article instead of read, play the audio file below!

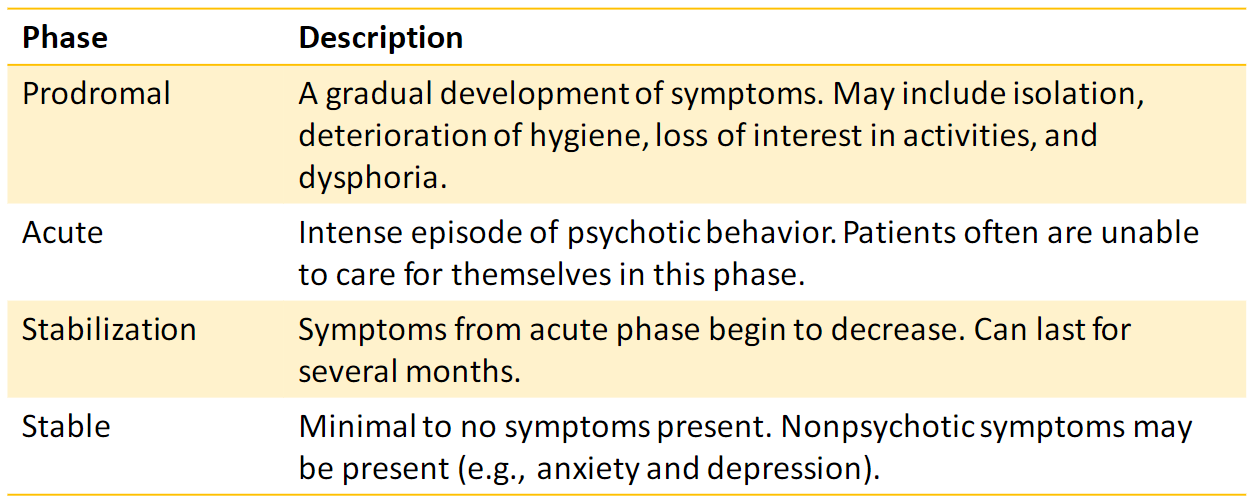

Schizophrenia is a thought disorder involving psychosis and a complex mix of symptoms. Common symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized speech. There are four stages of schizophrenia: prodromal, acute, stabilization, and stable.

The true pathophysiology of schizophrenia remains unknown. Two neurotransmitters that are thought to be involved are dopamine (hyperactivity in some areas of the brain and hypoactivity in others) and serotonin.

Antipsychotic medications are the first line for treatment. These medications target the dopamine and serotonin receptors in the brain. In addition, some have affinity for other receptors such as acetylcholine, histamine, and adrenergic receptors. This creates a unique side effect profile for each medication in the antipsychotic class. Something important to note is that ALL antipsychotics carry a black box warning (BBW) against use in older adults with dementia.

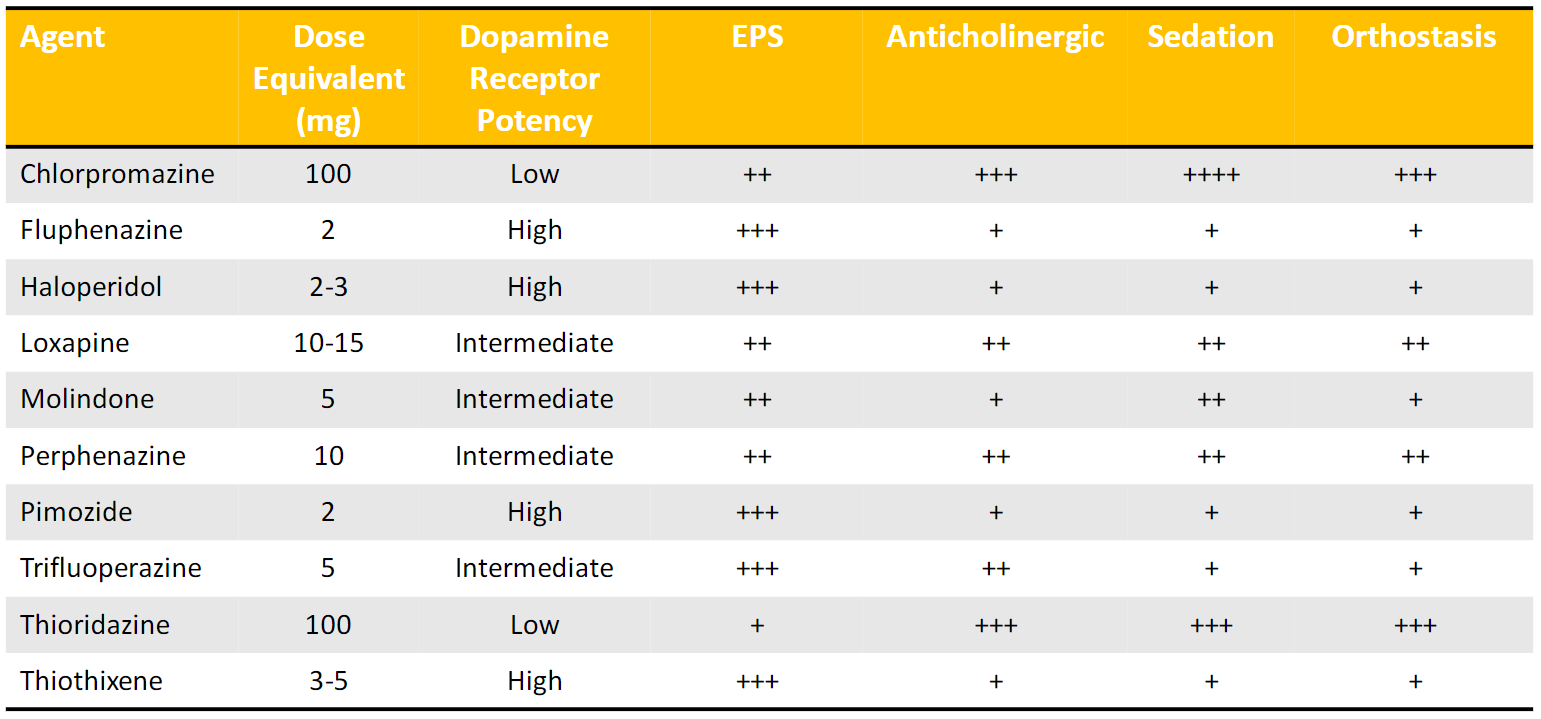

First generation antipsychotics (FGAs)

FGAs, or typical antipsychotics, have a 2-3 times greater incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared to the second generation antipsychotics. These medications elicit therapeutic benefit in patients with schizophrenia by antagonizing a variety of receptors, mainly dopamine. Antagonizing the receptor prevents (or inhibits) the normal response produced by the binding of dopamine to the dopamine receptor.

Below is a table of the FDA approved FGAs and characteristics relating to each medication. The side effects are explained later in the post.

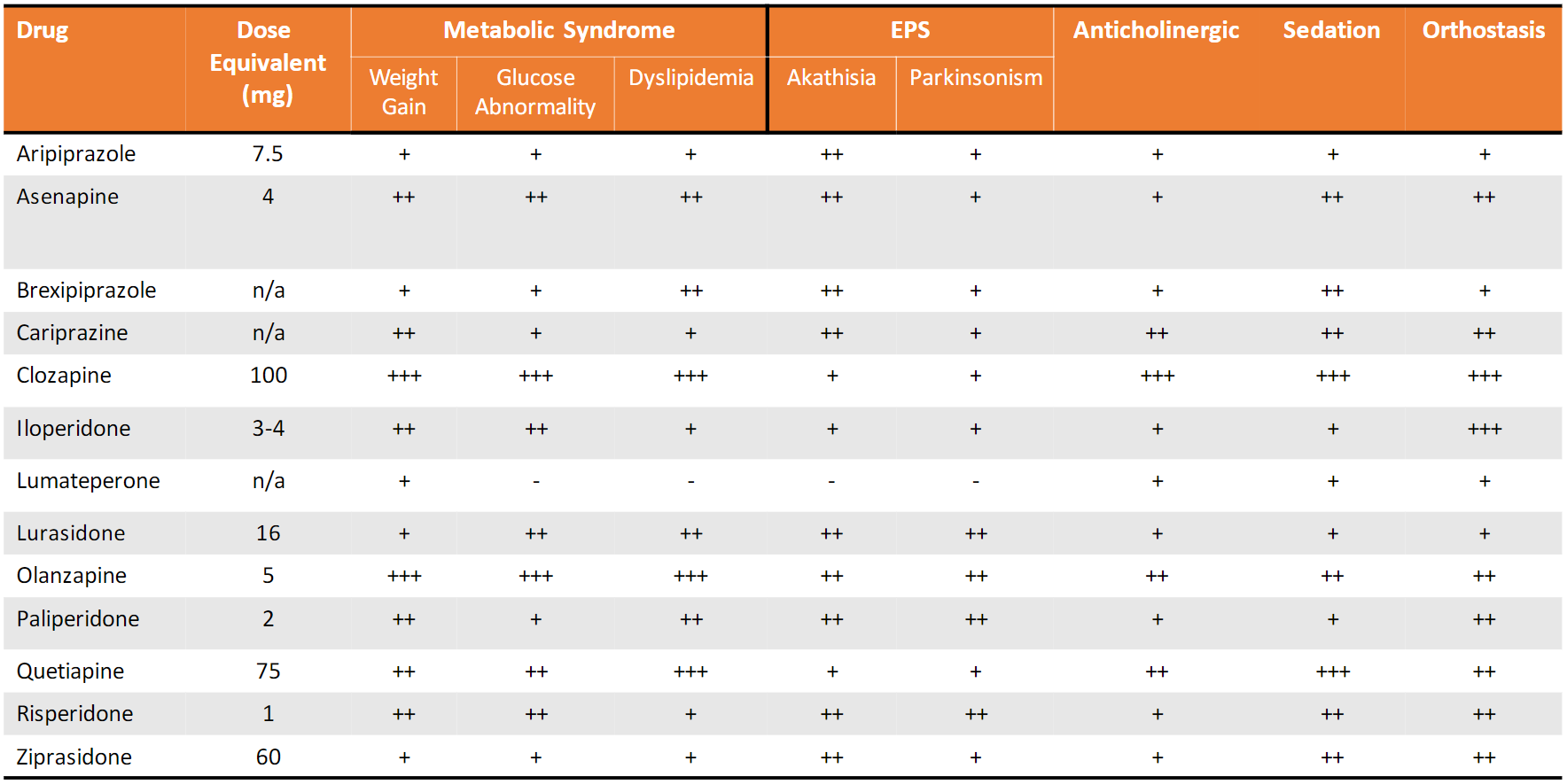

Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs)

SGAs, or atypical antipsychotics, were designed to minimize EPS. This group of medications is preferred by physicians and patients with schizophrenia for many reasons:

- SGAs have a faster dissociation from the dopamine receptors. This minimizes side effects that occur due to the antagonism at the dopamine receptor.

- Some medications in this group have partial agonism at the dopamine receptors (produces a response as if dopamine itself would bind to the receptor). This is thought to aid in reducing hyperactivity at D2 receptors in the mesolimbic neurons.

- SGAs are more selective for dopamine receptors, meaning they have less affinity for other receptors that produce side effects.

- The risk of tardive dyskinesia is reduced with SGAs

- SGAs have the ability to antagonize serotonin 2A receptors which may improve negative symptoms of schizophrenia and reduce the risk of EPS.

Despite all of the benefits listed here, SGAs have been associated with metabolic syndrome and new onset diabetes. Lifestyle counseling and a healthy diet are important when taking these medications.

Below is a table of the FDA approved SGAs and characteristics relating to each medication. You can compare the frequency of side effects with the FGA medication table above.

One important note is the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program with clozapine. This requires all prescribers and patients on clozapine to be registered in the REMS program. Why? Because clozapine has a severe neutropenia (agranulocytosis) risk. In short, patients who are prescribed clozapine have to have regular monitoring of their complete blood count to ensure they remain safe while taking the medication.

What are the side effects?

EPS

- Parkinsonism: presents as bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, or akinesia. If you notice your patient has these symptoms, it is recommended to lower the antipsychotic dose or change to another medication in the class. If neither is effective, oral anticholinergic agents have shown to be effective to resolve symptoms.

- Dystonia: usually an acute presentation of torticollis (spasms of the neck muscles), laryngospasm, and oculogyric crisis. Acute episodes are best treated with intramuscular anticholinergics.

- Akathisia: presents as the inability to stay calm or still; restlessness. It is recommended to reduce the antipsychotic dose or change to a different agent. Lipophilic beta blockers have been shown to have some benefit for akathisias.

- Tardive dyskinesia: involuntary movements that present in patients on chronic, higher doses of antipsychotic therapy. A common sign is inappropriate movements of the tongue (watch a video here!). Tardive dyskinesia is often irreversible. One strategy for resolution includes lowering the dose of medication, however, this must be weighed against the worsening of schizophrenia symptoms. Another option is to switch antipsychotics. There are two medications (valbenazine and deutetrabenazine) that are the first FDA approved drugs for tardive dyskinesia.

Dopamine Receptor Potency

- Low potency = more non-specific side effects (notice the trend of plus signs in the chart above)

- High potency = less effects from other receptors, but more EPS and hyperprolactinemia. Hyperprolactinemia is due to antagonism at dopamine receptors. Can lead to breast enlargement, galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, infertility, and menstrual changes.

Sedation

- Due to antagonist activity at histamine receptors

Anticholinergic effects

- Can be any of the following: dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, urinary hesitancy

- Tend to be dose dependent

- Think anti-SLUDGE – an acronym for Salvation, Lacrimation, Urination, Defecation, Gastrointestinal distress, Emesis

Orthostasis

- Hypotension upon standing

- Clinically defined as a fall in systolic blood pressure greater than 20 mmHg or a fall in diastolic pressure greater than 10 mmHg within 3 minutes of standing

Other common side effects of antipsychotics

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (more common with high potency FGAs)

- Sexual dysfunction

- Weight gain

- Diabetes

- QTc prolongation

- VTE (case-control study data, seems to be greatest in first 3 months of therapy)

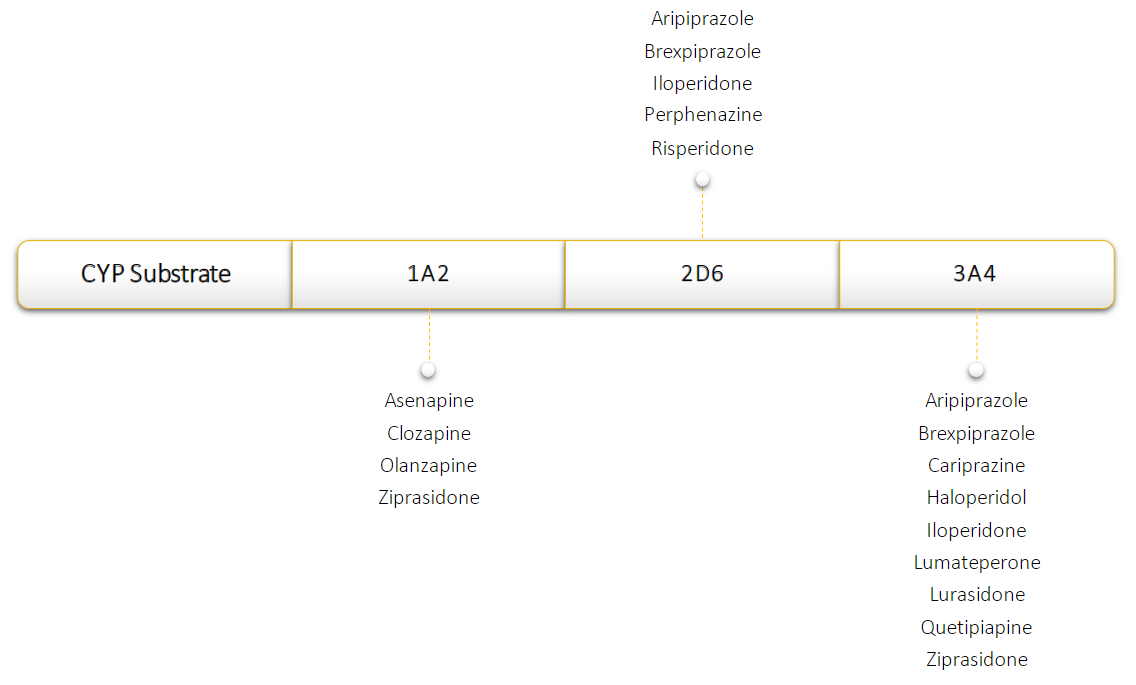

Medication interactions

From a pharmacy standpoint, we are always on the lookout for drug interactions. Patients are often on multiple medications. A handful of medications can inhibit or induce the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system. The CYP system is one of the systems responsible for metabolizing drugs in the blood stream.

- Inducers of CYP enzymes may require an increase in antipsychotic dose. This is due to faster metabolism of the drug. Smoking can induce CYP1A2.

- Inhibitors of CYP enzymes may require a decrease in antipsychotic dose. This is due to slower metabolism of the drug. Fluconazole can inhibit CYP3A4.

- ***Special note: risperidone is a prodrug. This means the parent compound is inactive, and only after being metabolized by CYP into 9-OH-risperidone does the compound have activity in the body. CYP inducers increase the activity of prodrugs (by creating more active metabolite faster) and CYP inhibitors decrease the activity of prodrugs.

Below is a figure of the antipsychotic medications and which CYP enzymes they are substrates for:

Clinical practice perspective from an inpatient hospital pharmacist:

- Titrations with antipsychotics are important and emphasized in drug references. However, in the acute setting, many providers are aggressive with their titrations. Keep this in mind when moving forward in your rotations and clinical practice. Patients in acute episodes often require higher doses of medications, and providers may desire a faster titration schedule than our guidelines/references suggest.

- Keep a keen eye, a questioning attitude, and check for those drug interactions!

References

- Crismon ML, Smith T, Buckley PF. Chapter 84: Schizophrenia. In: DiPiro JT, Yee GC, Posey LM, et al., eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2020.

- Keepers GA, Fochtmann LA, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2020. Available at https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi. books.9780890424841.

- https://cpnp.org/guideline/essentials/antipsychotic-dose-equivalents

- https://psychopharmacopeia.com/antipsychotic_conversion.php

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532938/