Beyond Capacity: Intro to Cognitive Load Theory

Imagine your brain as a bucket, constantly filling up with new information each day. What happens when you fill it up too much? The abundance of new information is either “spilled” out in overflow or “drained” into a separate storage for safe keeping and future retrieval. This is the focus for the instructional design theory called Cognitive Load Theory (CLT).

First coined in 1988 by Dr. John Sweller, CLT assumes that our brain – the human cognitive system – has a limited working memory (WM)1. WM refers to the memory used when actively engaged in thinking about a problem. Think of it like a sticky note that your brain creates for new information so it can organize it with existing information and file it under long-term memory (LTM)2,3. The overall goal of CLT is to prevent cognitive overload of our WM (or the overflow of our buckets) and optimize our LTM to enhance learning.

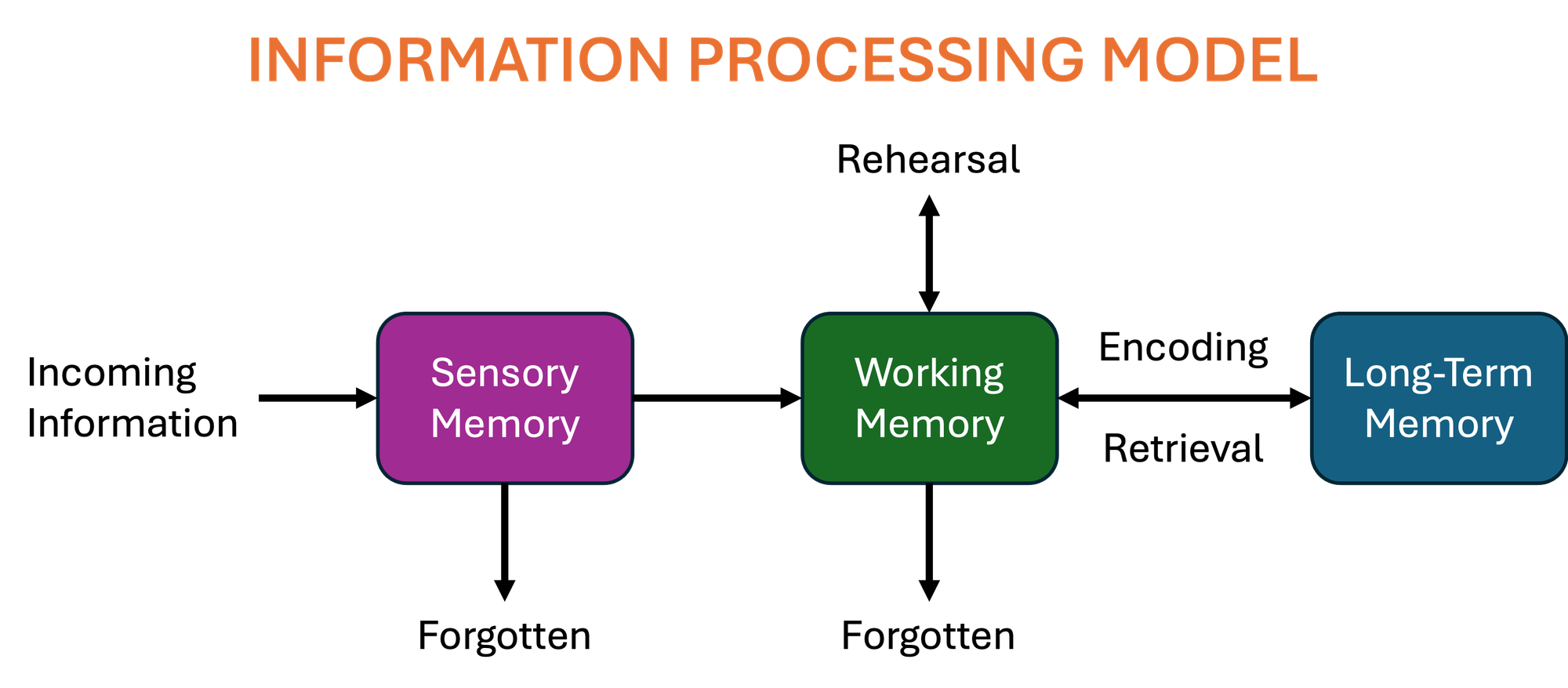

Below is a simple diagram outlining the general path of how our brains process and remember specific information:

When we receive new information (through reading, hearing, feeling, etc.), our sensory system passes some of that info onto our WM. Some of that initial information is ignored and forgotten.

Once our WM receives info from our senses, it can decide to either rehearse (repeat) that info and then encode it into our LTM, or it can decide that it's not important and can be forgotten. We can also take information from our LTM (retrieval) and rehearse it with our WM - as is often the case when we study for exams or quizzes. You can think of our WM as a quality control worker, deciding and filtering what important information it receives a wants to keep or forget.

Unfortunately for us, our WM doesn't have a very large capacity. It's often seen as a limiting factor for how much information someone can process and internalize at a time. This can pose a lot of issues especially within the academia realm where it is vital to try and understand as many concepts as you can to excel in exams.

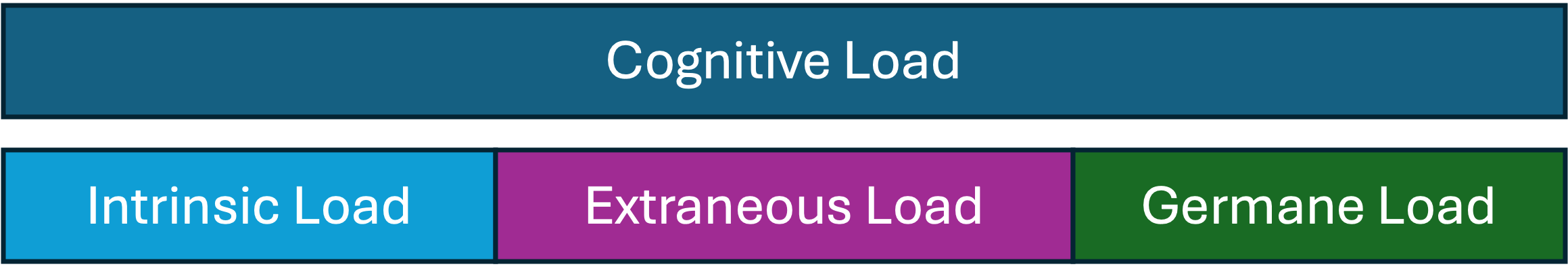

One of the most relevant applications for CLT is within healthcare education. With hundreds of clinical trials, new medications on the market, and scientific advances, it’s increasingly difficult for today’s students to learn all the information there is to know. Often what happens is the WM quickly reaches capacity and students experience cognitive overload resulting in information being lost or forgotten. CLT helps to manipulate the three types of cognitive load – intrinsic, extraneous, and germane – to prevent working memory from reaching its limit4.

Intrinsic load often refers to the natural or inherent difficulty of the subject matter. Basically, how complicated is the topic? Take for example a university level 400 course in mathematics. This course is usually taken by advanced level students and may review complex calculations, calculus, statistics, etc. The intrinsic load that this level 400 course has will be naturally higher compared to a university level 100 course which may include basic arithmetic.

Generally, this type of load is considered fixed and cannot be altered without changing the difficulty of the material4,6. For example, to reduce the intrinsic load of complex concepts in an advanced clinical course, a student could go back and review concepts in the pre-requisite course. Sequencing (presenting parts of a concept in order) and breaking down highly complex content into smaller, more manageable portions are other ways to reduce intrinsic load.

Extraneous load refers to the load that is imposed by instructional design and procedures and are non-essential to the task at hand3,4,6. It can include all of the distractions that one is susceptible to when attending a lecture or course. If you've ever had a class where the professor completely overloads the slide with words, numbers, and pictures, you know exactly what extraneous load is.

This is the type of load that should be reduced as much as possible to optimize learning. When lecture materials contain too much information and too little time is spent explaining, the extraneous load imposed dramatically increases. Providing insufficient guidance which forces learners to employ trial and error-type problem-solving also inadvertently increases the extraneous load.

Germane load refers to the resources that our brains use to manage the intrinsic load. Essentially, how easy is it to link current knowledge to additional information being processed. It helps to integrate new information and create or modify coherent cognitive schemas3,4,6. This type of load should be optimized, as it will help increase the amount of memory devoted to organizing into LTM.

One common example to help optimization of germane load is by including dedicated reflection time into lectures. Reflection can allow students time to rehearse complex material and file it away into their LTM. Additionally, students may utilize a design principle called the self-explanation effect. An example of this is if you are teaching about the human cardiovascular system, consider presenting students with an animation of how the heart works and provide prompts that ask them to self-explain the underlying mechanisms. By having students elaborate using their own thought processes it helps to improve learning through higher a higher germane load.

So, how exactly can we reduce the amount of cognitive load and optimize learning? If you ever find yourself teaching a lecture, training a co-worker, or presenting in front of an audience, consider some of these techniques to help improve your teaching and reduce cognitive load for your audience!

Try to reduce the amount of information (if possible) that you are presenting to only what's necessary. Sometimes, keeping things simple is more beneficial for both teacher and student! Focus on quality and clarity.

Furthermore, try to avoid being redundant. Think back to school. Have you ever had that one professor that would pull up their slide deck and immediately start to read word-for-word from it? Often times, it's not necessary to read the information that is on the screen. While some learners do best through auditory means, it may be redundant to read all the information you have on your slide.

If you have an important concept you want learners to understand, try to utilize tools such as bolding, italicizing, or underlining that important concept. In PowerPoint (and many other presentation programs) you have so many tools at your fingertips. You can even try highlighting what you want learners to know! This draws attention to the concept and reduces the time it can take to fully process that information.

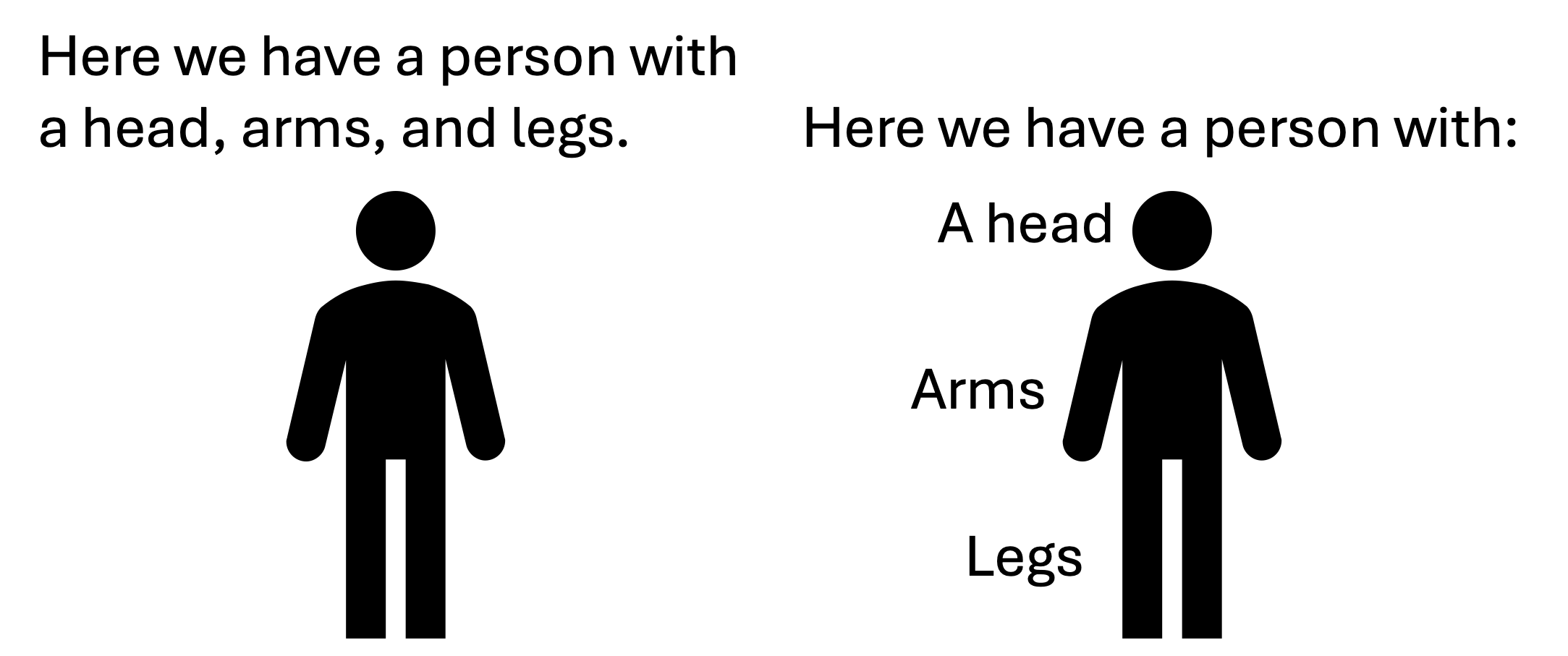

This can be a very good way to reduce the cognitive load for learners if used correctly. When you're designing your presentations or lectures, try to make it as easy as possible to understand from a learning perspective. If you have relationships you want to point out, design it so that the learner doesn't have to try hard to piece together information. Here's an example:

Do you see what I'm doing here? On the left, I've made a statement on the body parts I would like to point out on the image I'm showing of a person. On the right, what I do instead is match each body part I want you to know about and place it next to the actual body part. The image on the right is supposed to help you take less time trying to relate the words to the image.

This can be a very helpful technique, especially in healthcare where there's lots of diagrams and images in relation to words.

This final tip is similar to the previous one, but more so talking about the amount of time you spend on each concept and how you time the concepts between each other. If you have two important items you want learners to know, and those items are related to one another, present them in a stepwise fashion one after the other. You want to avoid jumping from one topic to another without warning.

Being aware of the overarching concepts in CLT can greatly benefit both the educator and the learner. In order to effectively teach and train students in these highly complex healthcare curricula, we can utilize CLT and our knowledge on the three types of cognitive load to prevent overload and optimize learning.

References:

- Sweller J. 1988. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn Sci 12:257–285.

- Working memory is limited. University of Minnesota Center for Educational Innovation. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://cei.umn.edu/teaching-resources/leveraging-learning-sciences/working-memory-limited

- Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, Ten Cate O. Cognitive Load Theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach. 2014;36(5):371-384. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.889290

- Van Merriënboer J, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):85-93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03498.x

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Chapter: Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Spence, K. W., & Spence, J. T. The psychology of learning and motivation (Volume 2). New York: Academic Press. pp. 89–195.

- Fuhrman J. Cognitive load theory: Helping students’ learning systems function more efficiently. The International Institute for Innovative Instruction. June 6, 2017. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.franklin.edu/institute/blog/cognitive-load-theory-helping-students-learning-systems-function-more-efficiently.

*Information presented on RxTeach does not represent the opinion of any specific company, organization, or team other than the authors themselves. No patient-provider relationship is created.